I’d like to thank Douglas Adams for introducing me to “The Zen Method of Navigation” from his oh-so-fun book Long Dark Tea Time of the Soul.

Instead of trying to get directly to his intended destination, protagonist Dirk Gently chooses to follow someone who looks like they know where they’re going. Gently’s method is rooted in his belief of the fundamental interconnectedness of all things. He assumes that everything in the universe is related, so following a seemingly random person can still lead him to where he needs to be—even if it’s not where he thought he wanted to go.

Sometimes, his approach works surprisingly well, leading Dirk to unexpected clues or connections in his investigations. Other times, it leads to complete chaos or absurdity, which often still serves the narrative in humorous or enlightening ways.

"I rarely end up where I was intending to go, but often I end up somewhere that I needed to be." -Dirk Gently

I use this method of decision making more than one “might” think prudent. This may have something to do with being dyslexic. I don’t always end up where I want to go anyway. Did he say “left-right-left,” or “right-left-right? Goddammit.”

Having three children and a very busy life, I know better than to employ the Zen Method in everyday life. Also I believe that the (Type A, not Zen) phone/GPS navigation app is arguably the most universally useful tool of modern existence for getting directly to your destination.

So, I mostly employ the Zen Method as a “solo” practice in places where outcomes are not required—specifically, reading. A place to be free.

There are so many highly regarded books that one could conceivably just have a list and go one by one to ensure they have thoroughly or appropriately or provably engaged with the best literature in the cannon, but that has more to do with what other people think. If there is only one place that I can employ my intuition fully, it is with reading.

I was late to Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House which had been suggested to me so many times that my oppositional defiance disorder reared its ugly head and I relegated the book to the land of Book Club Books, which aren’t bad, but their front row placements in bookstores and embossed gold read-me stickers make them feel like telemarketers to me and I go the other way.

I know, I know. What a dope I was.

In the Dream House employs an experimental and fragmented memoir format that mirrors the disorientation and complexity of trauma. The narrative is divided into short, titled chapters, often beginning with “Dream House as…” (e.g., “Dream House as Folktale Taxonomy”), each adopting a distinct lens or motif to examine her experience in an abusive queer relationship.

Using second-person narration, Machado immerses the reader in a memoir of abuse, queerness, and survival, while integrating elements of folklore, pop culture, historical research, and literary analysis. The nonlinear story unfolds like a mosaic, with these (amazing) footnotes that add meta-literary commentary that push the limitations of language and narrative itself. It’s these footnotes that elevate the text and make me swoon. It feels like the chorus in a Greek play, or the crowd cheering after a goal.

(These supporting footnotes often feature references to Stith Thompson’s Motif Index of Folk Literature, a cross reference database of the world’s folktales.)

Machado draws parallels between her lived experiences—particularly her abusive queer relationship—and the archetypes found in folklore. By referencing motifs cataloged in Thompson's index, she places her personal trauma within a universal, almost mythic context, like "Bluebeard" (Thompson Index, C611: Forbidden Room) to the secrecy and control her abuser exerted over her, illustrating how her experience echoes a long tradition of narratives about power, fear, and violation.

And as you’re reading, you can’t help but think, Wait, my mom had a room we couldn’t go into….

And when Machado invokes D110: Magic Transformation God (Goddess) assumes form of a wolf. Irish myth: Cross; Greek myth: to discuss how trauma reshapes her identity, casting her survival as both a loss of innocence and an act of transformation, you think: Oh, shit, I’ve had one of those when I went from my highest self and turned into a fierce wild animal hell bent on… And just like that a motif from the annals of time becomes your own.

I wonder if I’m making sense.

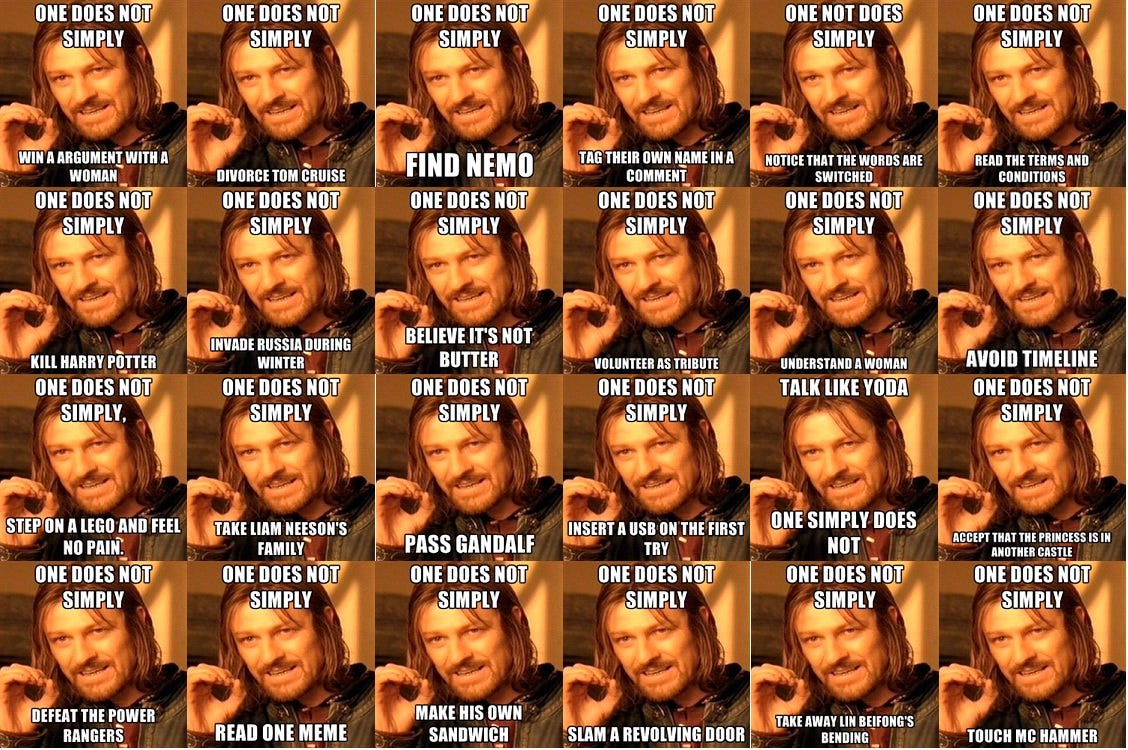

I love thinking about this. Imagine how a meme is created and then repeated and changed— they are like folktales in this way. The motif of Boromir saying “One does not simply…” gets used over and over in different ways in the same way the Looking Back on a Journey motif (Stith Thompson Motif Index entry D672) is repeated over and over in folktales.

This is the original meme: In a scene from the first LOTR movie, The Fellowship of the Ring, Boromir, played by Sean Bean, explains to the council: “One does not simply walk into Mordor. Its black gates are guarded by more than just orcs. There is evil there that does not sleep.” And then, making a circle with his hand, he says. “The great eye is ever watchful.”

Look at how it changes while the motif stays the same:

This motif gets reassimilated into each meme creator’s (storyteller’s) version.

Here’s mine:

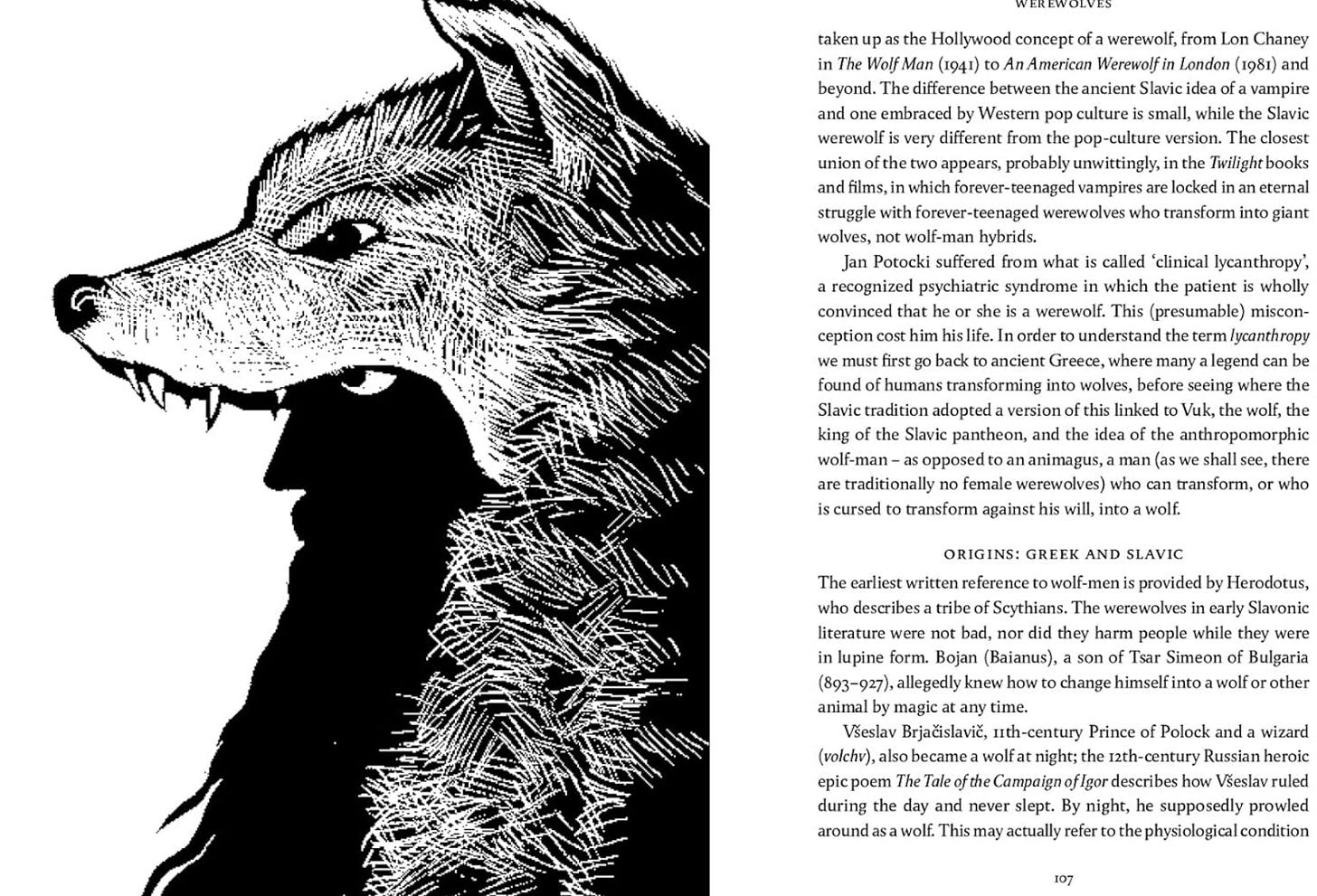

The same way we might consume a series of memes, One does not simply read one folktale either, especially if they are being told about thousands of them by Stith Thompson (say three times fast). The transformation section really spoke to me, so I spent days flipping back and forth in the dusty pages and indulging in translated folktales until I arrived at “The Blue Butterfly,” (a vampire story) from The Slavic Myths by Noah Charney and Svetlana Slapšak. This gorgeous book is full of folktales situated in their historic context and illustrated by gorgeous woodcut images.

How lovely is this?

I will never, ever outgrow books with pictures but I might put it down when a 50th birthday present arrives from one of my besties who lives in Budapest. She sent chocolate coated marzipan bonbons (OMG), some Hungarian face cream (Do I look younger?), and a book— Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb. Not only do I get some Hungarian history and a common link to my dear Eszter with this book, but I get to read a delightfully written book that has a flexible narrator. It creates this feeling of being sucked deeper and deeper into the story which is one of my favorite sensations as a reader.

Szerb starts out in a third-person omniscient that shifts into first-person present and then moves to first-person past. It’s a story within a story within another story like Russian nesting dolls. Oh, it’s delightful and reminds me of the blurred timelines and dreamlike qualities of stories like If On a Winter’s Night a Travler by Italo Calvino or Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut.

And that’s the thing about this helter-skelter reading journey—it’s pure delight. By realeasing myself from the straight path or checking off some literary to-do list, I stumble into unexpected connections, new obsessions, and the occasional chocolate-coated marzipan bonbon. From folktale motifs to fragmented memoirs to Hungarian novels that twist and turn like a dream, I find that the joy isn’t in reaching some imaginary destination of "well-read." It’s in the meandering, the discovery, and the freedom to let one book lead to another, trusting that wherever I end up is exactly where I need to be.

Do you use the Zen Method for anything? If so, are you also dyslexic?

Ciao,

n

Much love and appreciation for reading.

Sharing, leaving a comment, and subscribing all help me grow this Substack.

I use a method of reading that I think of as synchronicity: the universe tells me what to read next. For example, last week I came across references to Margaret Atwood thrice. The universe is clearly telling me to read more Atwood. This seems closely related to your Zen method, and no, I am not dyslexic, but I am a busy mom, so, one does not simply make a plan and stick to it.

Whimsy and purpose on the page!