Alright, I’m vertical again and revising a short story that is kinda surreal. My main character takes a journey into another world and then comes back. The world she travels to is not reality, it’s an alternate version of a life she is enchanted by. This is a pretty common occurrence for all humans, I think. Life is hard and we need breaks from harsh realities. We can all get there one way or another—a daydream, a puke flu, a few drinks, meditation, mushrooms, TikTok, a book—and we all do it, some more than others.

But how do I get my character there? Are there rules to a surreal world? I went poking around and here’s my back of the napkin attempt to explain surrealism to myself.

One of the first surreal states that I ever remember reading is in chapter 15 of “Little House on the Prairie,” called FEVER ’N’ AGUE. This is the scene when Laura and her whole family get malaria. Not one of them can help the other, they’re so sick. (It’s terrifying to think of parents being so sick they can’t help their own children, and for young children to not have the help of their parents.)

Anyway, here’s where Wilder moves her characters to an altered state. I looked at each move she made to understand how she was building the other surreal malarial world. Here’s a snapshot of what I noticed. [It’s me in the bold brackets]

Laura did not exactly go to sleep, but she didn’t really wake up again for a long, long time. Strange things seemed to keep happening in a haze. [Wilder asserts the altered state of haze, a blurred landscape.] She would see Pa crouching by the fire in the middle of the night, then suddenly sunshine hurt her eyes and Ma fed her broth from a spoon. [three disconnected facts] Something dwindled slowly, smaller and smaller, till it was tinier than the tiniest thing. [This is a vague reference to what? like something abstract is disappearing. The aperture becomes so tiny it can’t be seen.] Then slowly it swelled till it was larger than anything could be. [Now something abstract is growing, and the aperture is so wide it lets in too much light to focus.] Two voices jabbered faster and faster, then a slow voice drawled more slowly than Laura could bear. There were no words, only voices. [Here are disembodied voices that don’t say anything intelligible. They are too fast or too slow demonstrating Laura’s inability to come to the surface of her illness.]

Surreal is one of those words I use all the time, but until my most recent exploration, I can say that I’ve never actually known the full meaning of the word. I would have said it meant, not quite real, and I’d basically be right. But there’s so much more to it.

So, where does the word surreal mean and where does it come from?

Merriam-Webster defines surreal as: marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream

also: unbelievable, fantastic

and an internet search reveals that surrealism came about after the terrors of reality in WW1 and in concert with Freud in the 1920s when he started talking about how the irrational dream state illuminates the conscious mind. By 1924, Andre Breton created the Surrealist Manifesto outlining what surrealism meant in art. Hallmarks practices of Veristic surrealism connected seemingly disconnected objects, rejected form and traditional structure and defied expectations to arrive at new conclusions as a method of exploring emotional and existential gravitas (while whimsy, a sister to surrealism, later explored emotional lightness and human connection). The other aspect of surrealism, which I ignore here, is Automatist surrealism where the art is based in feeling only and is not meant to be analyzed. It is only a representation of a brain and hands creating a product fueled by impulse and feeling, without attention to form or subject.

So, what does Veristic surrealism look like in art?

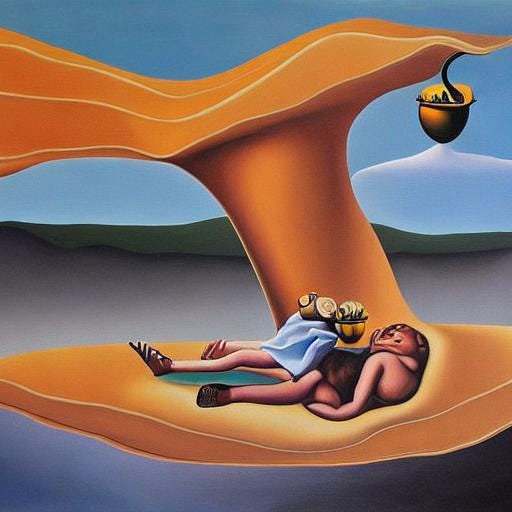

Here’s an AI-generated, Salvador Dali-inspired, scene of Laura’s fugue state.

In this image, the outside world is the size of an acorn at the top right and the figure is suspended in an undefined shape set apart from the ground or the sky. The figure is made of four human legs, is partially underground, and has a face like a mole.

In looking at these two versions of surrealism, the image, and the passage, what might I take away as a definition of the surreal?

Here, I identify the concepts I notice from the two versions and practice by creating my own sentences based on my observed “rule” of surrealism. Feel free to play around, too. I feel stiff attempting this.

Disproportion. Some things will be unnaturally large and others unnaturally small.

Her breasts spilled out on all sides of the bikini made for a child. The white triangles of fabric looked like pasties over her nipples held fast by invisible threads.

The language, fragmented, not taking full shape, white space b e t w e e n lett3r$, or nonsense, no cents, can’t smell a polypiac in the cold coripal of time.

Abstractions of bodily form and metamorphosis. She burned. Her center dissolved and she was only arms and legs. Her hands, giant spoons, dripped broth into the cherry mouth crying from the bedclothes.

Juxtaposition - amalgamations, setting displacement, subverting hallmarks of typical settings and objects. A burning cold wind blew down on the tops of their toes which poked out from under their hats. A steel door hung from a cloud on the garden path.

Alter the typical vantage point or separate the body and mind. Her voice, high and thin, eeled into the ears of the men upstairs. She slept under her bed in order to never be disturbed.

Consider what some of the hard rules of reality are.

Gravity: what goes up must come down.

Sun goes around the earth in 24 hours.

Senses: the eyes see, the ears hear, the nose smells, the tongue tastes, the skin feels.

Emotions: sad news makes a person cry, and a joke conjures laughter.

States of Matter: Puddles are wet. Paper is dry. Clouds are mist. Floors are solid.

People: Babies don’t know language and can’t walk. Adults walk and talk.

Now break those rules.

If I break all the rules of reality, the world I make becomes unrecognizable, but if I only break some of them, my world is made of recognizable parts but has unpredictable correlations like a dream.

“James and the Giant Peach” by Roald Dahl is another familiar example of surrealism. James comes from the real world and stumbles upon one very disproportionate thing in his aunts’ garden, a giant peach. This one out-of-the-ordinary object hijacks the entire story into a world that defies convention.

Some modern examples are “Nightbitch” by Rachel Yoder where a mother changes form (Think Kafka), and one of my all-time multi-genre favorites, “Still Life with Woodpecker,” by Tom Robbins. I’ll leave you with a few lines about his typewriter from his prologue and you can consider if you think he works with Surrealism, her younger sister Whimsy, and/or their cousin Phil.

I sense that the novel of my dreams is in the Remington SL3—although it writes much faster than I can spell. And no matter that my typing finger was pinched last week by a giant land crab. This baby speaks electric Shakespeare at the slightest provocation and will rap out a page and a half if you just look at it hard.

Thanks for exploring a corner of the surreal with me.

-n

So interesting - makes me think of stream of consciousness (Woolf) and Stein’s mind-muddling syntax. Both from the post WWI and ascension of Freud era. Reality was harsh....

I want to turn this into a poetry prompts for my workshopping group ❤️